The Paradox of Privacy.

Hello! This post is the second instalment of a six-part series I’m creating as part of the Global Media Planning module for my Masters in Marketing and Digital Communications. Each instalment will tackle a different question from the assignment brief, and I’ll be sharing my progress along the way. The final assignment submission will bring everything together by focusing on three of the most important questions. Whether you’re interested in global media planning or just curious about the behind-the-scenes of a master’s assignment, I hope you find these insights useful. Thanks for following along!

The Paradox of Privacy: If No One Is Watching, Do Ethical Concerns and Personal Privacy Really Matter to Global Media Planning?

In this post, I’ll explore how this paradox plays out in today’s digital ecosystem, and what it means for media planners trying to navigate the tension between precision targeting and ethical responsibility. I’ll examine why consumers sacrifice privacy for convenience, how platforms encourage this behaviour, and why ethical media planning matters even when no one is watching. I’ll also look at the complex global regulatory landscape, offer practical strategies for ethical planning, and argue that privacy isn’t just a compliance issue, it’s a strategic asset that builds long-term trust and brand value.

Unravelling the Privacy Paradox.

While people frequently express concerns about their privacy, they often willingly trade personal data for benefits such as convenience, personalisation, or a sense of social belonging. As Harris notes: consumers express a lot of concern about their privacy online in surveys. At the same time, very few engage in privacy-protecting activities. (cited in TWIPLA 2024).

This disconnect is frequently engineered by design. Platforms like TikTok embed data collection seamlessly into their frictionless user experiences, making it effortless for users to share data without conscious awareness. Users often accept these terms because they want instant access to apps, free downloads, or enhanced features, valuing immediate benefits over potential long-term privacy risks. Artificial intelligence then uses these vast datasets to deliver hyper-targeted advertising, often without users fully understanding the extent or implications of the information they are giving away.

Surveillance Capitalism.

As a consumer, I enjoy personalised recommendations on Spotify or Netflix, but I’m uneasy about the sheer volume of data required. Zuboff’s (2019) surveillance capitalism framework warns of systems that commoditise behaviour at scale. It raises ethical red flags, not just for users but for the media planners who rely on this model. Mark Weinstein talks more about Surveillance Capitalism in his Ted X Talk (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ted X - Surveillance Capitalism (Weinstein 2020)

Global Media Planning and Regulatory Complexity

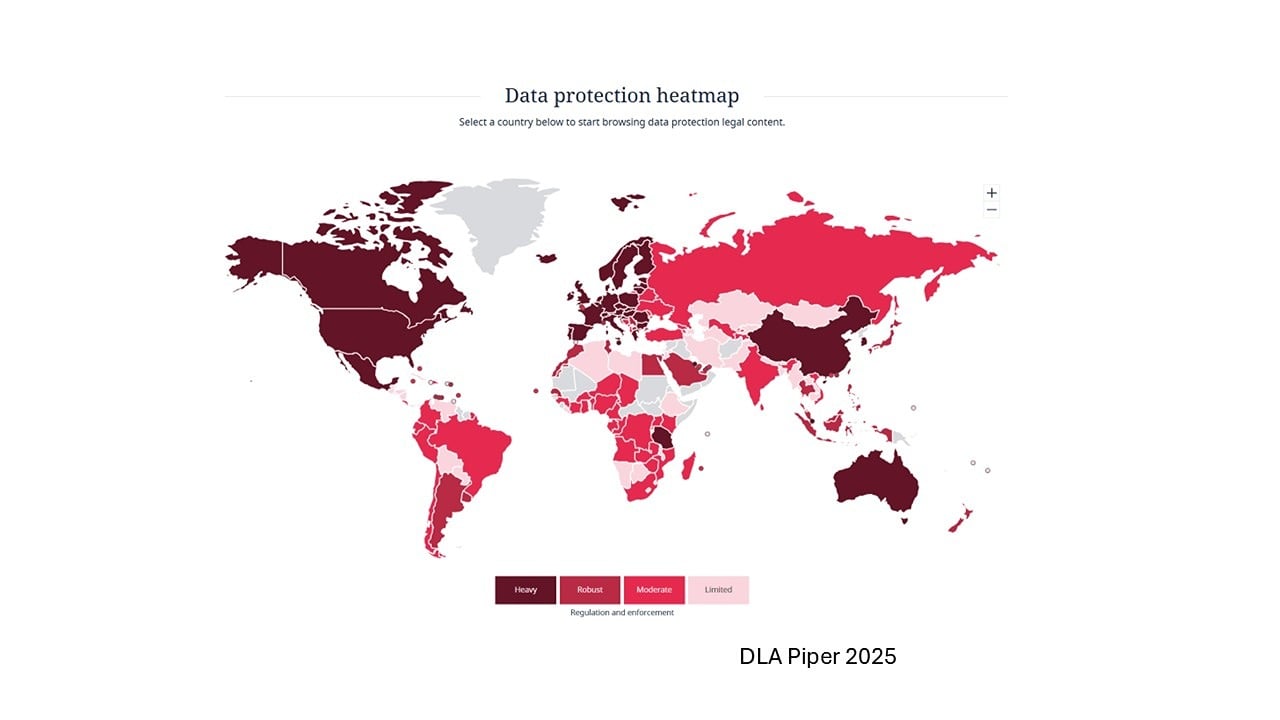

Data empowers global planners with precise targeting, but international regulations complicate the landscape. The EU’s GDPR demands strict consent, while the US relies on state laws like California’s CCPA. In Asia, India’s DPDP Act signals increasing regulatory assertiveness (DLA Piper 2025). To illustrate this complexity, DLA Piper’s data protection heatmap is shown in Figure 2.

Beyond regulation, cultural nuances matter: a campaign respectful in Germany may feel invasive in South Korea. Brands using generic privacy notices risk seeming disingenuous, eroding trust and brand equity. Ethical media planning requires more than compliance; it demands cultural sensitivity and contextual awareness (Team EMB 2024).

If No One Is Watching, Does It Still Matter?

Absolutely, because real ethics show when no one’s watching. Ethical media planning is about safeguarding long-term strategic value:

Trust is fragile – the much publicised Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal shattered trust and drove regulatory reform (Criddle 2020).

Regulation evolves – with data protection and privacy laws advancing rapidly (DLA Piper 2025).

Reputation is viral – one data breach can destroy years of brand equity overnight.

As a consumer, I prefer brands that explain data use clearly and respectfully. Transparency isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s a competitive edge. Zuboff (2019) reminds us that exploitative data use may deliver short-term gain but erodes long-term trust and legitimacy.

Strategic Responses to the Paradox.

Global planners must respond both ethically and strategically. Best practice includes:

Privacy-by-design – build privacy into planning from the outset. Only collect essential data (TWIPLA 2024).

Transparent consent – replace legal jargon with clear, honest language (Ambekar 2023).

Geo-specific adaptation – tailor privacy experiences to regional laws and norms. Cookieless tracking is one promising solution.

Ongoing ethical audits – regularly review for compliance and public acceptability (Prosper 2022).

Cross-border standards – collaborate on international codes of conduct to bridge legal gaps (DLA Piper 2025).

These aren’t just ethical obligations, they’re smart brand strategies. In a crowded, cynical marketplace, respecting user privacy builds meaningful differentiation.

In Conclusion: Privacy And Ethics Are A Strategic Asset, Not A Constraint.

The privacy paradox isn’t a loophole to exploit. It’s a challenge that calls for leadership. Brands that embed ethics into their media planning will be more resilient in a world of shifting expectations and rising scrutiny. As Soller (2020) argues, trust is more valuable than data. In global media planning, privacy is no longer a constraint; it’s a strategic differentiator. The real question isn’t whether planners can operate in grey areas, but whether they should, especially when long-term value depends on integrity and respect for the people behind the data.

Thanks so much for reading. I’d really love to hear what you think, whether you agree, disagree, or just want to chat about media planning (or assignment writing!). Feel free to comment on my LinkedIn posts (where I’ll be sharing each part) or drop me an email. Your feedback will be a huge help as I decide which three posts to polish up for my final assignment. Looking forward to connecting!

Bibliography

Ambekar, M. (2023) The Ethics of Data Privacy in Digital Marketing. LinkedIn. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ethics, data, privacy, digital, marketing, mandar, ambekar [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

Center for Journalism Ethics, University of Wisconsin, Madison. (n.d.) Global Media Ethics. Available at: https://ethics.journalism.wisc.edu/resources/global, media, ethics/ [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

Council of Europe (2018) Guidelines on Safeguarding Privacy in the Media. Available at: https://rm.coe.int/guidelines, on, safeguarding, privacy, in, the, media, additions, after, adopti/16808d05a0 [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

Criddle, C. (2020) ‘Facebook sued over Cambridge Analytica data scandal’, BBC News, 28 October. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-54722362 (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Data Protection Commissioner (2018) Case Studies. Available at: http://www.dataprotection.ie/en/pre, gdpr/case, studies [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

DLA Piper (2025) Data Protection Laws of the World. Available at: https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/ (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Prosper, J. (2022) ‘Privacy Audits and Compliance Metrics: Measuring Success Beyond Checklists’, ResearchGate, February. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390756367_Privacy_Audits_and_Compliance_Metrics_Measuring_Success_Beyond_Checklists (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Sage Journals (2023) A Longitudinal Analysis of the Privacy Paradox. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14614448211016316 [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

Soller, F. (2020) Trust is the ultimate currency. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2020/08/27/trust-is-the-ultimate-currency/ (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Team EMB (2024) Digital Advertising Challenges: Ethical Dilemmas. EMB Global. Available at: https://blog.emb.global/digital-advertising-challenges-ethical-dilemmas/ (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

TWIPLA (2024) The Privacy Paradox: Torn Between Love and Fear. Available at: https://www.twipla.com/blog/the, privacy, paradox [Accessed: 26 June 2025].

Weinstein, M. (2020) Surveillance Capitalism and Democracy. TEDx Talks. Available at: https://youtu.be/AoYC4ogezE4 (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Zuboff, S. (2024) ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power’, Journal of Information Ethics, 33(1), pp. 84–85. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/3070764499 (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

About the author

Hello - I'm Rachel. I am currently studying for a master’s in Marketing and Digital Communications at Falmouth University. This series on Global Media Planning is part of an academic assignment, so if you’ve ever wondered what university assignments in this field look like, you may find these posts offer a useful insight. I invite you to follow along for future instalments and would love to hear your thoughts or comments, please feel free to share your perspectives on LinkedIn where I am sharing the series.

Comments